Hello dear friends and readers. I’m writing to you from my current perch in the Alfama (the old Muslim quarter of the city) on my last night here in Lisbon. I know I still owe you a second Porto round-up post, and many other posts that I have thought about writing but haven’t yet put to paper, but I will beg your indulgence of my absence these last few days – I have, as they say, been living a lot of life. I will definitely have more thoughts to proffer tomorrow from the airport and reflections later on over these next few weeks. For now, however, in a fit of nostalgia – or really most likely, saudade – and a burst of gratitude, I’m going to post a few of my favorite shots from this wonderful trip. I hope you enjoy – more soon.

Rounding Up Porto, Part 1

Hello friends! I’m writing to you happily but not without a healthy dose of longing (saudade, is that you?) because Aaron and I left our cute little perch in Porto for the northern climes of Braga (it’s definitely hotter than expected). While we are definitely delighted with our new digs in a building that dates to 1513 (!! – don’t worry, they’ve been stylishly updated), I have to admit I already missed Porto. Simply put, I loved Porto. It is such a beautiful place, not only because of its youthful effervescence burbling up with all the different musicians on the streets and the seagulls calling throughout the day, but also because of the way its slightly mysterious as I talked about in my last post. Whatever the case, I think Aaron and I found our favorite Portuguese city (though, never fear! Lisbon is a veeeeery close second). I thought I’d do a brief little recap of all that we say, ate, and did over our last few days in Porto – which is actually quite a lot, but I will admit is for both of our memories ;)

The panorama from the top of the Torre dos clérigos.

On Saturday, we started the day with a panomramic view of the city from the monumental Torre dos Clérigos (with a much more detailed museum exhibit than expected). After that, we visited the divine tinned-fish mecca of Conservas Pinhais & Cia in Matosinhos, a suburb outside of Porto city. We got the recommendation to do the factory tour from our friend Imogen (hi Imogen!) and let me tell you: if you go to Porto, this tour is a not-to-miss. Completely charming and totally delicious, the tour started with a walk through the twentieth-century deco offices of the original company (in use until pre-pandemic), continued with a couple of well-produced and frankly heart-wrenching videos about the fishing industry, followed by a uniformed traverse of the factory floor where the sardines are cleaned and canned, and finished with an absolutely delightful tasting of Pinhais’ signature “Nuri” sardines (our favorite were the spicy ones). It was informative and just an all-around treat.

Suited up and ready to can some sardines at Conservas Pinhais & Cia.

Sardine heaven (the butter was sardine compound butter).

From there, we headed to the Confeitaria de Bolhão, a classic café, for an afternoon sweet treat. We split a piece of chocolate cake and a bolo de berlim, which is essentially an egg dough croissant or doughnut filled with egg custard. I paired mine with a galão, or a milk coffee, and Aaron got an espresso. The confeitaria is just across the street from the Mercado do Bolhão, Porto’s iconic open-air market, with all the classic fruit and vegetable stalls. Though our shopping that afternoon did not include them, we did end up going back on Monday to get the amazing fruit cups filled with freshly cut fruit for €2,50. Walking back from the market, we stopped in the gorgeous and historic São Bento train station, covered in blue and white azulejos before rounding up our evening on the Rua das Flores with dinner at Candido dos Reis. We topped off the night with a night cap at Base Porto.

Some sweetness at Confeitaria de Bolhão.

Mounds of garlic at the Mercado de Bolhão.

Base Porto from above.

On Sunday, we had a slow morning in our lovely apartment before walking around the neighborhood. After coffee and breakfast on our porch, we ended up stopping at the iconic Livraria Lello, which supposedly inspired JK Rowling. We ended up at the Fundaçao Serralves , Porto’s contemporary art museum and park, in the evening, where we saw an amazing exhibit of Alexander Calder and Joan Miró – the wire sculptures were amazing! We ended up getting home later than expected that evening after an okay meal at the Italian place Grazie Mille. Overall, it was a very sweet weekend that just revealed all the amazing things we saw, tasted, and experienced in beautiful Porto. I have more to write (including a mini-tour of Porto’s Jewish quarter), and plan to finish this in another post with lots more historical context and detail. But for now it’s late and I’m off to bed. Até amanhã!

A Calder at the entrance of the Serralves Museum.

Posting from Porto

Hello dear readers! I am writing to you right now from the delightful little patio of our Airbnb in Porto. My apologies for missing the last couple of days of posts – I have to say I’ve moved a bit into vacation mode so I’ve been a little bit more lax about my writing practice. However, I did just want to share a little bit about Porto so far, since it is truly a delightful place.

The view from the patio of our Airbnb.

We arrived here on Friday, after about a three-and-a-half-hour train ride from Lisbon. The train was overall uneventful except for some brief moments of boisterousness from a family that included a grandma, uncle, two small children, one tween, and two very distracted parents. Though we were scheduled to arrive in São Bento train station, which is beautifully covered in azulejos, after a transfer from Campanha (pronounced by the train conductor as “campan-yaaaaa” in a very cartoon villain like voice) that arrived later than expected, we decided to take an Uber straight to our Airbnb on Rua da Belomonte. Classically, we discovered once we arrived that we happen to be staying where the medieval Jewish quarter was located (more on that soon).

Kicking back on the train.

Beautiful São Bento station.

From there, we walked around the winding and hilly streets of our neighborhood before heading to services at the Porto Synagogue, named Synagogue Kadoorie Mekor Haim, located in the neighborhood of Lordelo do Ouro e Massarelos. The services were a bit more Orthodox than my preference and observance level dictates, but the inside of the synagogue itself was gorgeous, tiled in azulejos and gilded letters, and offered an interesting counterpoints to my experience in the much less ornate Lisboa synagogue. For example, though both services were more on the Orthodox side of things, the rabbi in Lisboa gave a brief drash in English whereas the rabbi in Porto did not give a drash and his announcements were given in rapid, French-accented Hebrew. I found it interesting that the assumption was that every person in the congregation would understand this. I was lucky to find a buddy for services in an older woman from the States who said she and her husband travel to Porto every for six months on a transatlantic ship. She, like I, found the services more Orthodox than our personal practices, but she said that in Porto, the choice is between this synagogue or nothing. Overall, I found it a much more welcoming community than the one in Lisbon, differences in observance aside.

The outside of the Porto synagogue, all I could capture since I had to turn my phone off before entering.

From the synagogue, we headed back to our neighborhood, where in a few short hours the streets came alive with young people. Porto has the vibe of a university town much more than Lisbon, and this was palpable as we found a bar to sit at and have dinner across from a miradouro that also acted as a stage for the band performing a mix of Bowie, Arctic Monkeys, and Stevie Wonder covers. So far, I’ve found that there’s a lot more music on the streets of Porto than Lisbon. It has the sort of magical, half-hidden vibe that I experienced when I lived in Granada – like you can tell the city has delightful, surprising things to reveal to you but it won’t tell you when they will appear. Perhaps it’s the magical Douro river that traverses the city, or perhaps it’s the romance of a medieval port city-turned-university town. Whatever the case, even from our first day here I have felt that Porto is very special. There’s more to share about what we did on Saturday (including a tour of a sardine factory!!), but I will save that for another post. Until then!

A beautiful view from the miradouro near our house.

A sweet shot of us + the view :)

Tidbits on Tourism

Last night, over a truly, deeply delicious diner at Cantinha do Avillez in the Baixa-Chiado neighborhood, Aaron and I had a really interesting conversation. Part of the conversation related to the work that I do as a scholar of cultural studies, and I explained to him that a central theme of my work is to study narratives. This post is not so much about that conversation, but rather about my continuing thoughts about this idea of narratives. And as we went to Belem to eat the famous pastéis de nata and see the Monasteiro dos Jerónimos (whose main monastery we did not end up getting into due to an online ticket debacle), I was thinking a lot about one set of narratives in particular: those of tourism.

The lines at Pasteis de Belem, the best place to get pastéis de nata near Lisbon.

Lots of people on the streets of Belem.

Happy people eating pastéis de nata.

Being in Lisbon in the midst of the high season, the crush of tourists from various non-Portugal countries is inevitable. While I’ve been here I’ve overheard French, English, Italian, Hebrew, Russian, and Arabic – just to name a few of the languages. And over the last couple of days, both in Lisbon and at Belem, I have been witness to and been on the receiving end of the disgruntled lisboetas who are (in many ways understandably) frustrated about having their daily routes and routines overwhelmed by people who are not from there. This has gotten me thinking about tourism, its nasty effects, and my own reflections on what constitutes responsible tourism (if there is such a thing). But especially connected to yesterday’s post and the various Jewish artifacts that I’ve seen throughout my time here, I am also thinking a lot about the ways that Jews and Jewish history in particular are presented here – not to mention the role this plays in perpetuating particular narratives about Portuguese identity for both cultural and economic motives.

As a point of comparison, when I lived in Spain, I remember often feeling that in many sites of touristic interest there was a deep disconnect between the treatment of the lustrous past of the Sephardim and the lingering ignorance around a modern Jewish presence. For example, I distinctly remember visiting major Jewish sites associated with the Red de Juderías (Network of Jewish Quarters) such as the extant medieval synagogues in Toledo, which we proudly displayed as part of Spain’s important legacy of multiconfessional coexistence, yet would then go out into the street and hear people use the term “cerdo judío (Jewish pig)” to describe someone’s unruly behavior. Some of this disconnect is, of course, due to complicated histories of imposed Jewish absence and modern concerns about security. In my experience, the narrative promoted by these touristic sites (of which there are many) is one of benevolent ownership, often without real reparative work that speaks to the similarly longstanding legacy of anti-Judaism in the country as well.

The highly elaborate Manueline façcade of one of the side doors at the Monasteiro dos Jerónimos.

Here, though, my experience of the ways Portugal’s Jewish past is narrativized and promoted by the Portuguese tourism industry is different. First, there is actually quite a bit less material to look at – thus my excitement to share the two stones seen at the Convento do Carmo. Perhaps because of this, the amount of exhibition space afforded to Portugal’s Jewish past is much more abbreviated – such as at the Museu de Lisboa, which while it does an excellent job attesting to the presence and contributions of marginalized people of color in Portugal’s past, there is only one TV monitor that offers some information on the medieval Jewish community there. Similarly, there is one road in the Alfama neighborhood that has taken on the name of what was once a whole quarter of the city (Rua de Judiaria). And second, I have to wonder whether Portugal, like Spain, sees a need to promote certain narratives of its national self through its Jewish past. In Spain, there is a long history of telling specific stories about Jews at key moments of sociopolitical upheaval – such as the renewed interest in studying Spain’s Jewish history during the Segunda República, or Francisco Franco’s use of a totemic “Judeo-masonic socialist” as the antithesis to his dictatorial vision – even without there being a real Jewish presence.

The tomb of Vasco de Gama, the Portuguese explorer who “discovered” the route to India in 1498, in the church of the monastery.

In Portugal, these narratives function very differently, and there seems to be a comfort with briefly mentioning Portugal’s Jewish history at these sites and then moving on to other objects of seemingly greater interest, such as Manueline churches, relics from the Christian reconquering of Lisbon, and the remains of Roman temples and aqueducts. As I attempt to read more about why this might be the case – and whether this lack of focus on the Jewish history of Portugal goes beyond just a lack of material history -- I have more questions than answers. And they are questions that tie into my own reflections on what it means not just to be a tourist, but especially a Jewish tourist, in this country.

Tomorrow we are off to Porto, and I’m looking forward to sharing more reflections then – until then, boa noite!

Finding clues in between the stones at the Convento do Carmo

Hello friends! I am back today after a brief two-day pause on my posts. The reason for the pause is that things got a bit busy yesterday as my boyfriend, Aaron, came into town and we went into touring high gear. We moved from the wonderful Airbnb I was staying at in the Luz neighborhood to another delightful one right smack dab in the middle of Baixa-Chiado on Rua da Madalena. In between our shlepping of stuff from one Airbnb to another we did some touring: on Monday, we walked from the Miradouro São Pedro de Alcantara down through Chiado to the Praça do Comércio, where the Portuguese ships departed for Africa and the New World. Yesterday we spent the afternoon ogling the many beautiful objects in the Convento de Carmo, the remains of a 15th century convent that has remained un-reconstructed since it toppled the Lisbon earthquake in 1755 and was converted into the Carmo Archaeological Museum (Museu Arquaeológico de Carmo); briefly stopping at Caza de Vellas Loreto, which has been selling candles since 1789; and ending the day atop the Castelo São Jorge, a medieval castle that has been occupied by the successive populations of Lisbon since the Phoenicians – plus one that has killer views of the city, particularly at sunset. All in all, it has been a whirlwind of touring the hills and valleys of this lovely city, much to our enjoyment (though definitely less so for our tired feet.)

The pillars at the edge of the world.

My cute lunch companion fresh from the States :)

Because of this, my research has tended toward the much more experiential – but this is not to say I haven’t been researching! Actually, I’ve been pleased how much that is relevant to my research has come up through this sightseeing, mainly in two key categories: Jewish and culinary material history. I know I still owe you a follow-up blogpost on the modern Jewish community here, which is forthcoming I promise! (I am waiting for some interesting insights I may be able to glean when we go to Porto this Friday and attend services there). Today, however, I thought I’d do a little recap for you as well as for myself of a couple of these amazing objects I’ve been lucky enough to see.

A shot from inside the burned out Convento do Carmo, whose remains now house the Museu Arqueológico de Carmo.

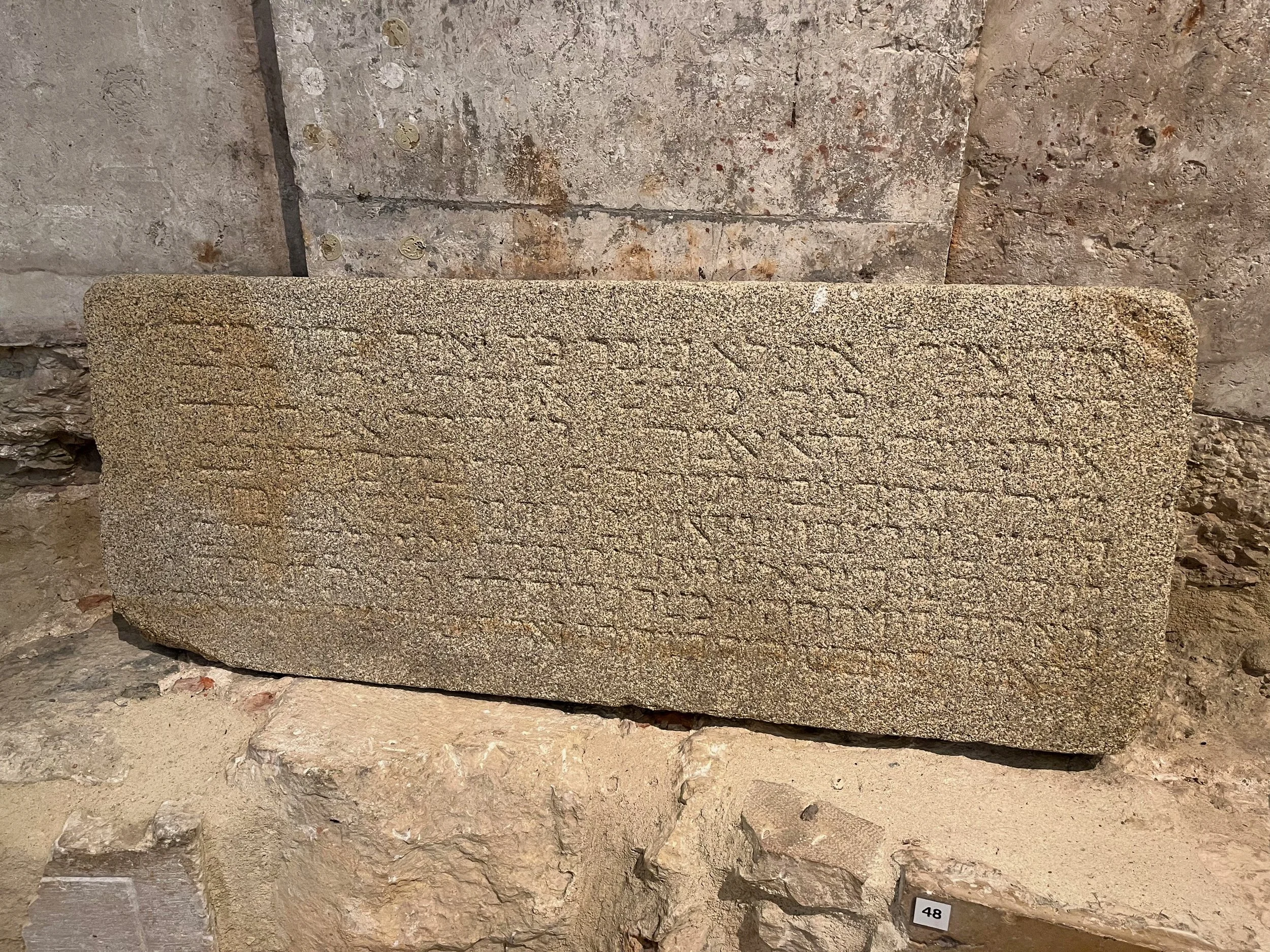

The first major pieces of relevant research material I got to see were at the Convento do Carmo. The collection at the archaeological museum captures a timeperiod spanning from the Chalcolithic period (approx. 3000 BCE “before common era”) to the 19th century. Among the various Christian stone tombs and seals, Chalcolithic arrowheads, and even two mummies of children that were collected from Perú in the 18th century, the Jewish pieces include the gravestone of Yehudah ben Rimok, from the 19th century, and a commemorative stone attesting to the founding of the Porto Jewish community from the 14th century. These two pieces, although separated by about 500 years in age, are evidence of the historical presence of Jews in Portugal – presence that is often forgotten in mainstream scholarship on the Sephardic Jewry, but which these pieces resoundingly affirm. And the commemorative stone for the Porto synagogue especially points us towards the historic presence of a vibrant and active Jewish community here in Portugal, especially reading the transcription of the stone translated to English:

The commemorative stone in question.

“Someone could say: how was a house of so much name not protected inside a wall? But this good one knows that I have a knowledge that is recognized from the high lineage. He is the one who keeps me because he declares to me without a shadow of a doubt that I am the wall where he is standing. Benefactor of his people, servant of God in his integrity, he built a house for his name of hewn stones. To the king he is second, to the head is reckoned by his greatness and in the presence of kings he rises. He is Rabbi Don Yehudah ben Menir, light of Judah, and he has authority. By order of the Rabbi that he live, Don Joseph ben Arieh charged the chief to the task.” (trans from display text in Portuguese)

Though its language is somewhat dense, in the oblique style of common of the panegyrics of medieval Hebrew poets, the inscription gives so much information about this community: who it looked to for spiritual guidance (Rabbi Don Yehudah), who it benefitted from financially (Joseph ben Arieh), and the location of the synagogue (outside the city wall). But through subtle hints, namely the honorific “Don,” we can also tell that this community was deeply integrated within the mores of the place in which it found itself. And hanging among the other pieces of stone on display, namely Christian in content and connection, this stone is easy to pass over. Yet by looking at it we see incontrovertible proof of not merely of a medieval Jewish community, but of a particularly Portuguese one.

As always, I promise more fun and updates tomorrow :)

A cute shot from the top of the medieval Castelo São Jorge.

Some Sunday Scenes

Although my post yesterday about my experience going to Shabbat services at Shaare Tikvah included a promise for a second follow up post, I admittedly did not have a lot of time to think about exactly what I wanted to write because my friend Imogen (hi Imogen!) came to visit and allowed me to play tourist for a day. And so, if you’ll pardon my delay in delivering you part two of my reflections on the modern Jewish community here in Lisbon and its relationship to the history I am studying, I thought I’d share a little bit of our itinerary from today in words and pictures. If I do say so myself, it was a very fun one – one that I highly recommend recreating if your path ever brings you here!

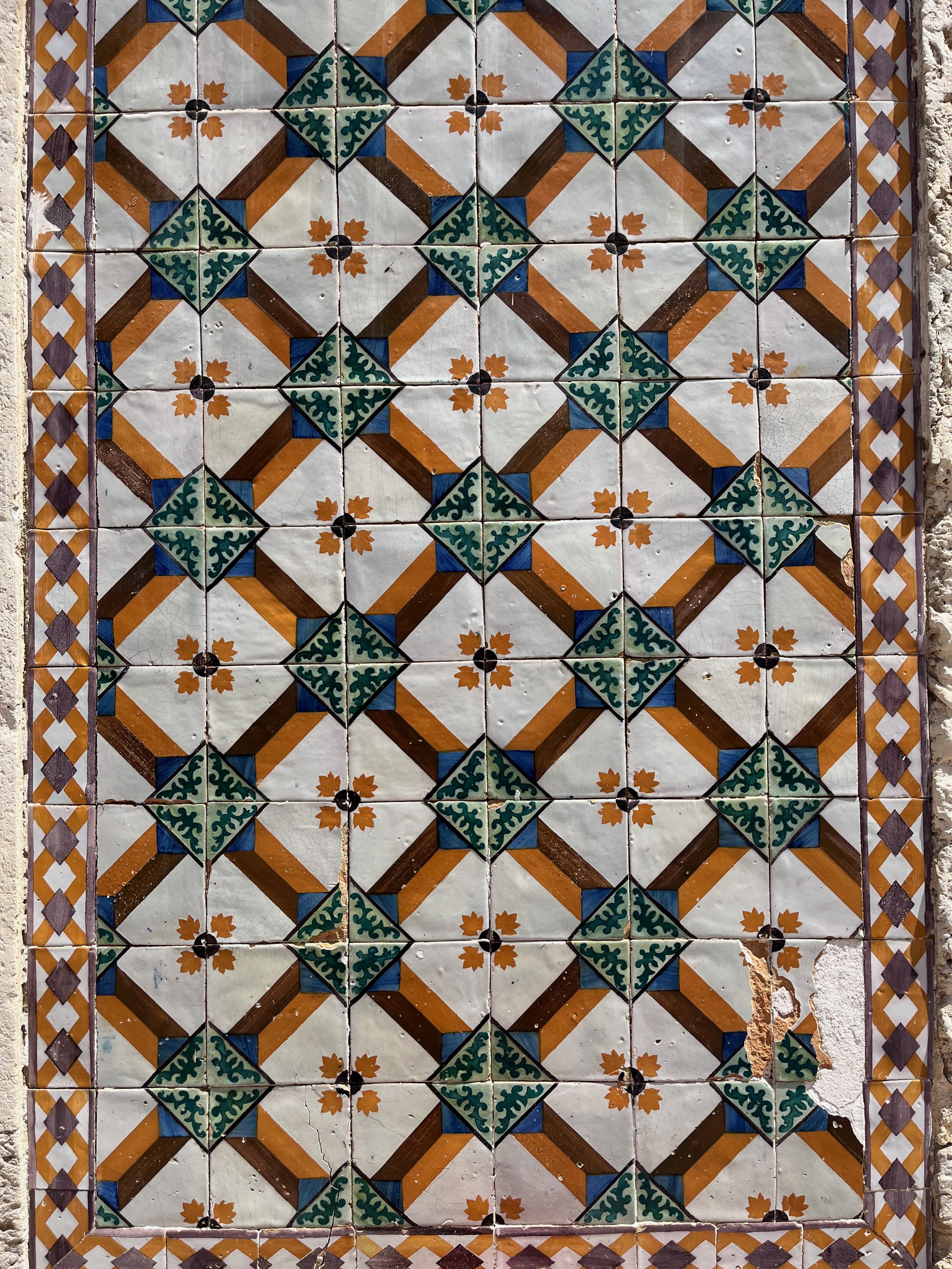

First we went to the Miradouro São Pedro de Alcantara, one of the most well-known and well-visited miradouros (lookout points) in the city. This was wonderful in itself, but the especially amazing surprise that came with it was stopping in the convent of São Pedro de Alcantara, which I had not been in. Part of what made it so amazing were the azulejos decorating the walls of the chapel and then the sepulchre of one of the head Inquisitors – quite the unexpected surprise! I have to do a bit more research to understand which head Inquisitor exactly it was, but it was certainly not what I was expecting walking into the building.

The extremely detailed inside of the sepulchre within the convent.

A close up of the text mentioning this individual’s role as Head Inquisitor “Inquisitor Generalis.”

From there, we stopped at the Confeitaria Nacional for a sweet little pick-me-up after traversing the hills to the lookout spot. Established in 1829, this sweet shop offers all of the classic Portuguese desserts, including pastéis de nata (the iconic cream tarts). We got a few fun sweet things to share, including a pastel de nata, a coelhinho (a small mouse shaped cake with what seemed like an almond base and a layer of sweetened egg yolk under a sugar shell), and – my personal favorite – a bola de ananas (pineapple cake). The pineapple cake was a vanilla sponge with canned pineapple in the layers and a barely sweet buttercream. Total heaven with a coffee.

The treats, from bottom left: pastel de nata, bolo de ananás, bolo de bacalhau, coelhinho.

From there we walked all around the Baixa-Chiado area, stopping at the Praça do Comércio where the ships for the New World left. From there, we walked up Rua Augusta and stopped in a few shops to get some clothes due to a luggage issue.

After stopping briefly back at home, we went back out in the evening to eat at the fabulous Penalva da Graça – so far one of my favorite restaurants here in the Graça neighborhood. We devoured an amazing shellfish rice – the best I’ve had here so far! – and a heavenly melon. And we were even kindly helped into our plastic bibs by our kind waiter. Another amazing meal.

The seafood rice of all seafood rices.

The wonderful inside of the restaurant — filled with folks from the neighborhood and a great little mural.

To finish off the day, we walked around the Graça neighborhood to the Miradouro de Graça and then back around through Martim Moniz to Rossio Square, and back up the city steps towards São Pedro de Alcantara once more. As we went, we stopped briefly at A Ginjinha de Carmo to get a sip of the sour cherry cordial that is a classic in town for a little night cap. We rounded out the night with a visit to the miradouro we started out the day with, and then went back home. Overall it was a day full of lovely bites and even better company. These places are definitely going on the list of Lisbon recommendations I plan to write for you all at the end of this experience! Now, I’m off to sleep – boa noite!

The menu at A ginjinha do Carmo.

The night sky and people chatting at the evening miradouro.

A Visit to Portugal's Jewish Present

On this blog, I’ve spent a lot of time writing about the Jews of Portugal’s past. From the remaining pieces of material culture attesting to their existence, to their rendering by non-Jewish artists, to conjectures about what they ate, I have spent a great deal of time on the past of Portugal’s Jews so far in this series of posts. Of course, you may say (and you may!) this is natural: Sara, you study the medieval Jewish community in Iberia. And I will say, yes! You are quite right, dear all-knowing reader. But this past Friday I was lucky to experience a little piece of the present Jewish community in Portugal by attending Friday night services at Shaare Tikvah, Lisbon’s sole brick-and-mortar synagogue (while it is not Lisbon’s sole Jewish community, there is also Ohel Jacob, the progressive community). I thought in tonight’s post I’d offer a brief recap of my experience there, to be followed by a later blogpost of some of what I’ve been thinking about this very important and complicated relationship between Portugal’s Jewish present and its past.

Services on Friday started at 7:30 pm. I ended up having to book it there in an Uber due to a previous meeting that afternoon going a bit later than expected. I quickly came home, changed into a more modest shirt as Shaare Tikvah is more orthodox, and hopped in the car, arriving at the synagogue a few minutes after the clock struck 7:30 pm. Worried at having the door closed in my face once again (flashback to Évora!), I tried to make peace with this potential outcome in the car – if I can get in, great, I thought to myself, and if not I will figure it out. With the momentary calmness this created, I hopped out of the Uber once it dropped me near the metro station of Rato, in the Prinçipe Real neighborhood of the city. The synagogue unassumingly resides a block away from the metro entrance, tucked neatly next to a Middle Eastern restaurant called Al Shami. It is so subtly there that it would be easy to miss, except for the gilded letters on the white door.

Luckily, I was not too late and I did not miss the entrance. There were also two men standing at the door – one clearly a security guard (a common fixture of European Jewish communities) and another who was similarly bulky but upon getting closer to him I realized he was the caterer, wearing a polo that had the words “Kosher catering” embroidered on the left breast. There were also two other couples waiting to get in, talking to the mustachioed security guard. As they spoke with him, the caterer asked me for my passport, inquiring whether I filled out the form online (which I had) and why I wanted to attend these services (I said for both ritual and research purposes). This is not the first time I have had this experience attempting to attend services in Europe; it is common practice to contact communities in advance and send your passport information, only to have it checked again at the door, for heightened security.

After my brief questioning and what I was told was an appreciated attempt to speak Portuguese, with an obrigada (thank you) I was let into the courtyard off the synagogue. The colors of white and gold appeared again on the inside wall, yet this time in a collection of epitaphs of beloved deceased community members. Across from this wall was the open door of the synagogue where people (some members, and some who I found out later were visitors) congregated. There, I was told to go upstairs to the women’s gallery in a friendly but firm way. I expected this as I knew ST was the more Orthodox community in town. Once upstairs, I picked up a prayer book from the table and found a seat in the rigid, high-backed wooden pews of the women’s gallery.

From my seat, I could see the bimah located in the center of the room (customary in Sephardic synogogues) and I faced the only decorated wall of the synagogue: the wall with the Ark. The wall is really an arch sitting on carved columns – the same design as the columns distributed throughout the main room and holding up the women’s gallery – a large stone arch emblazoned with the words “דע לפני מי אתה עומד (know before whom you stand)” in gold letters. Compared to the somewhat starkly plain congregation section and the straightforward bimah, this wall is particularly impressive. It formed quite the backdrop as a lay leader and then a rav-hazzan lead everyone through the prayers of kabbalat Shabbat. Though the prayers were in Hebrew, the rav-hazzan’s teaching about the Torah portion of the week was interestingly in English.

When services ended, I wished the women near me a Shabbat Shalom and found my way out. Although it was not my preferred or familiar style of services, I was glad to go and experience a living community here in Lisbon. Though I my ears pricked as I made my way out – to have an honestly non-kosher, but pork-free meal at Sumaya, a delightful Lebanese restaurant in the area – hearing English, decidedly American voices talking in the front hall. Definitely an unexpected twist of the language I thought would be spoken between congregants. It is this linguistic dissonance, and how it relates to some broader thoughts I have been forming about the relationship between past and present Portuguese Jewish communities, that I will cover in my next post. Until then – here’s to arriving late and still managing to get in anyway! And to a shabbat shalom.

A few bites for Shabbat

Hi everyone! Since it is late here and yesterday’s post was a little bit heavy — plus it is Shabbat, after all — I thought I’d bring back some lightness by sharing a bit about another big part of my experience here so far: the eating! I will be back in the future with a more complete list of restaurant recommendations, but for now here are a few visual “bites” of the food I’ve had since being here in Portugal. Desfrute (enjoy)!

Évora, the city of closed doors

In an attempt to make good on my planned itinerary for yesterday, today I went to Évora to visit the old judiaria (Jewish quarter) and look at some documents in the Biblioteca Pública da Évora – namely to see a 15th century ketubah up close and personal. It is a beautiful city yet on a variety of levels my experience of Évora was one of closed doors.

A medieval Jewish door on a street in Évora.

The day did start out well – I woke up early and on time to get to the train station, I caught every one of my somewhat confusing transportation connections, and in a fun turn of events I even realized when I got to Évora that my outfit unintentionally matched its quaint yellow-and-white walls. My plan was to go walk around the part of the city that constituted the medieval judiaria, followed the detailed explanation of it in Maria José Ferro Tavares’ As Judiarias de Portugal (The Jewish Quarters of Portugal), published in 2010. (Funnily enough, this was one of the books I was able to access in the Biblioteca Nacional back in Lisbon.) I thought this would be a great lead up to then viewing documents relevant to the very medieval Jewish community that lived there. Though, as you all know, I’ve had my challenges getting into archives this trip (and don’t worry – the rant post will come soon!), I was optimistic that this would be a great opportunity to view and experience medieval Portuguese Jewish material culture on a variety of levels.

An impressive barbican on the city’s medieval wall.

Yours truly, matching the city’s colors.

I arrived in mid-morning and did indeed have a good first hour and a half roaming the streets of the Jewish quarter, down the Rua dos Mercadores to the old medieval city wall, up Rua da Tamara (named for the appropriately food-related Hebrew word/name for tamar, or date) to the Rua da Moeda. Here’s the description I followed from Ferro Tavares:

“In a document from 1382, referring to the tenure of two stalls at the Gate of Alconchel*, the alley where they were found was said to belong to the barbican** of the fourteenth-century wall. This would mean that the road of the Jews would have extended for all of Rua do Tinhoso (now da Moeda) until its end, at the new wall. Here the Jewish quarter had a door***, the Gate of Palmeira on the side of that of Alconchel. This judiaria would be designated, in 1436, as the new judiaria. The judiaria of the 1400s was introduced on the Rua dos Mercadores (of the judiaria) by the Rua dos Banhos Velhos (Street of the Old Baths) that connected the Plaza (the current Plaza of Giraldo). Alleys without specific designation and backstreets were frequent in the space of the Jewish neighborhood, making locating them difficult today because they were integrated into the city’s architectural fabric” (Ferro Tavares 74).

And actually, following her directions, I was able to get a feel for what remained of the old Jewish quarter, including visiting a medieval door with a niche for a mezuzah. I had a sweet moment where I touched the mezuzah niche as is traditional for some Jews to do with a mezuzah upon entering a home – with a light brush and a kiss of the fingertips – which felt like a magical point of connection to a community centuries removed from me.

The sign on the Travessa do Tamara.

Rua dos Mercadores, a key street of the old judiaria.

The mezuzah niche up close — note its slight slant.

A long view of one of the winding streets of the judiaria.

However, I couldn’t help but notice that this door was no longer really a door – rather it was now a wall, blocked up with cement and unfortunately graffitied. Then, after visiting and communing with the old judiaria, around mid-day the vibe started to change. I don’t know what it was, but something just felt off. It started with me falling on my butt in the middle of the street as a biker pulled up short to the curb I was standing on, continued with the inexplicably cold affect of the servers at the café I ate in, and culminated when I walked up to the door of the Biblioteca Pública de Évora, only to be informed that today was a holiday and so the library was closed. This was particularly surprising given the fact that I had actually emailed directly with the archivist at the library and he made sure to mention that the library was a on a holiday on the 24 and 26 of June, but not of the 29th. And there was no notification on the website or on the city of Évora’s website about this closure either. Overall, these events were frustrating, but as I have learned here in Portugal – as with traveling generally – one must have patience; or as my dear friend and advisor Gloria would say in Ladino, pasensia!

The outside façada of the library, with a closed door.

Channeling this intention, I decided to make my way to the main cathedral of the city, the Sé, where I knew I would find a sculptural representation of medieval Jews on the door to the church, per Ferro Tavares’ book. The image in the book, though, is so close up I wasn’t sure where it was actually located. I finally found them after a second look at the door after my visit to the somber church. It turned out that the two Jews represented on the door, wearing the conical hats that Jews were decreed to wear, were to be found under the foot of one the twelve apostles also carved into the portico. In other words, more bad vibes – particularly connected to Jews. After this experience, a few hours before my train back to Lisbon was scheduled to leave, I must admit I could not wait to leave the city. Did I mention that the library shared the same plaza as the Palace of the Inquisition, which is now the city museum?

The building that was the old Palace of the Inquisition, now a city museum.

All said, I do genuinely hope to go back to the public library (perhaps on this trip, perhaps during future trips). And if you were to ask me, I do genuinely encourage you to visit Évora. But I think my experiences today and the sinking feel in my gut that grew throughout my day here made it clear that the history that I study is not always completely vibrant and happy. Anti-Jewish violence, persecution, and expulsion are key parts of the story of the medieval Sephardim. I firmly believe that studying this community, especially through and with food, expresses so clearly the vibrancy of this historic group of people and, as I noted yesterday, food can be a meaningful means to witness and bring to the fore the lives of so many often left out of what are considered more “official” historical accounts, who were relegated to marginalized status throughout time and place. I am convinced that food makes clear how little these “official” documents really can show us about the people of the past, which is why we so desperately need to study it and why I am so committed to doing so. But at the same time, sometimes being confronted with what remains of this history can feel really sad. And so today, it felt important to me to honor that feeling and how these closed doors bring it up – in the hopes of one day opening them again.

Always leaving room for a little sweetness to happen, even in the hard stuff!

With that note of tenuous optimism, I will leave it here for today. Until tomorrow – até amanhã!

*One of the medieval entrance through the city’s surrounding walls. Medieval cities in the Iberian Peninsula as a general rule have a defensive wall of stone, often erected under the Muslim rule of those territories, that encloses what many cities now consider the “old” city. Words like “cidade velha” or “casco viejo/ciudad vieja” usually tip you off on maps.

**A barbican is an outer defense on a medieval city’s wall, usually either a tower or a double tower over a drawbridge.

***Porta, in Portuguese, like puerta in Spanish, can mean both gate and door. For the purposes of this post I’m using door but please imagine in this case a big stone arch opening in a stone wall.

Cups, Plates, and Spoons – Oh My! A Trip through Kitchenware Chronology at the Museu de Lisboa

After a last-minute change of events, today I ended up taking a visit to the Palácio Pimenta at the Museu de Lisboa. I learned about this museum on the suggestion of a fellow Ladino avlante i amante (the name of my weekly Ladino group) and friend (thanks again, Torin!). I don’t know exactly what I was expecting, but what I ended up seeing was a material narrative of the evolution of diningware in Lisbon. And, as you all know I am a nerd about all things history and food, it was sooooooo cool! I definitely had what might be considered too much fun, geeking out and giggling to myself while creating captions for the scenes on some of the tiles.

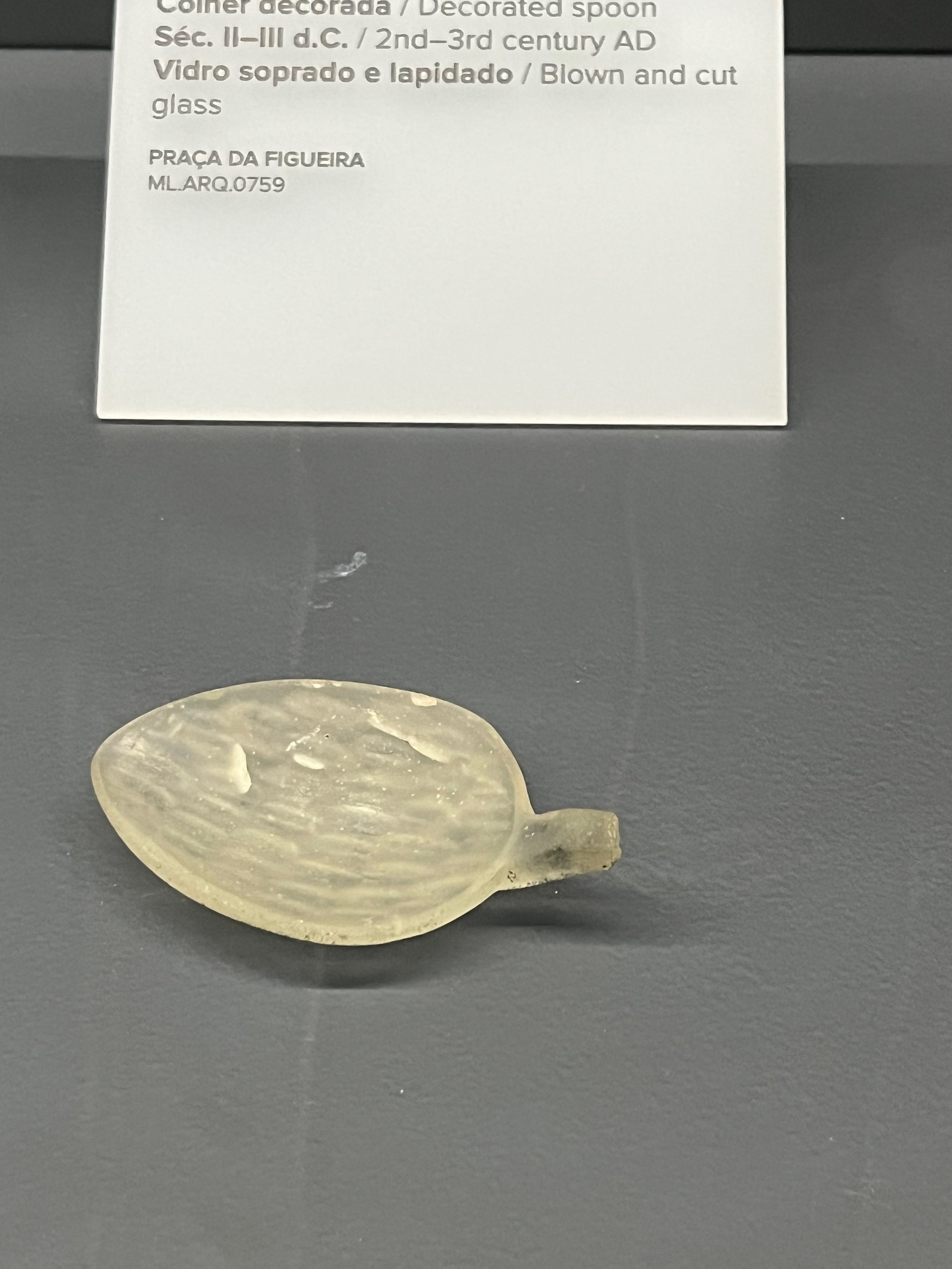

According to the website, the Museu de Lisboa was a result of a bringing-together of five locations that were relevant to Lisbon’s history, in order to “reveal Lisbon in different ways, to give the opportunity to know the richness of one of the oldest cities in Europe” (my translation). Not to put too fine a point on it, the museum really did just that – especially when it came to understanding Lisbon specifically through the serving-ware, flatware, and food-related ceramics that have characterized Lisbon’s eating history. Starting in the Roman period, when Lisbon was called “Olisipo,” according to the Odyssey, I saw amphorae (ceramic pitchers with a pointed bottom) for wine as well as fish and even a decorative glass spoon. Into the Islamic period, there were elongated jugs for olive oil, decorative glazeware bowls, and even a teapot – one of my favorite things I saw. From there, the museum included a brief mention of the history of the Jewish community of Lisbon, even including a map of the old big judiaria (Jewish quarter) there, but my main critique of this museum is that there was very little space dedicated to this historic community. In some ways, I was not surprised about this, because unfortunately we don’t much in the way of physical proof of the Jewish community as much of it was destroyed after expulsion and what was left was most likely decimated by the earthquake and fire that profoundly changed the face of Lisbon in 1755. But still, it would have been nice to have seen more than a singular video tower projecting a video dedicated to this important history. Not a surprising take from me, I know, but I’ll appreciate your indulgence of my favorite subject :0)

An amphora for fish — probably to make garum (a fermented fish paste that was used frequently in ancient Roman cooking).

A glazed ware bowl from the Muslim period.

A piece of a decorated spoon made from glass.

A beautiful bowl with 12 compartments from the 18th century.

One of the images included in the brief but informative video on the medieval Jewish community of Lisbon.

I will say, however, that the museum did succeed in giving a meaningful glimpse into the role that enslaved people in the history of Lisbon, especially as its related to material history. I learned that Portugal traded and shipped 13 million enslaved Africans to itself as well as its colonies – and on such a profound level it was the work of these people that gave shape to the culture of food in Portugal for hundreds of years by porting, preparing, selling, and generally being connected to food at every level of its life cycle. So often it is through food where the lasting legacy of those often forgotten in – or purposefully erased from – more “official” documents can be seen, not to mention the critical work of Black scholars and cooks such as Edna Lewis, Psyche Williams-Forson, and Michael Twitty that has given shape to and continues to profoundly influence the Food Studies field (ps - I highly recommend checking out Psyche Williams-Forson’s new book, Eating While Black that just came out from UNC Press). I appreciated that the museum offered a glimpse into this important piece of culinary history and that of the country of Portugal.

This amazing lady in the kitchen replica, scaling fish.

Towards the end of museum’s structured path, there was the piece de resistance: a full replica 18th century kitchen, renovated to include a surrounding of beautiful blue-and-white Baroque and kitchen-themed azulejos. It was like the star-studded finale of a show – just fabulous. And naturally, I topped it all off with an appropriately sweet Portuguese treat: a pastel de nata and a coffee at the Confeitaria Nacional. (The plates obviously inspired me, ha!) I’ve included some pictures so you can nerd out with me – feel free to let me know if any piece speaks to you in the comments below! I’m off to Évora for the day tomorrow and looking forward to sharing what I find there!

Pots and pans hanging in the kitchen replica.

Pastel de nata and coffee — the ideal sweet finish to any day of research!

Lisbon Week 1, in pictures

Hi everyone! It’s already been a whole week since I arrived – can you believe it?! Time is a weird thing. Here it’s felt like it’s been forever and also just a minute since I got here. In honor of my first full week here – and in part because yesterday’s post was a lot of reading – I thought it would be sweet to share 7 of my favorite things so far in Lisbon, accompanied of course by picture. Here goes nothing!

My seven favorite things (so far!) in Lisbon:

1. The gardens and outdoor concerts at the Fundação Calouste Gulbkenian.

2. The secret staircases into the Alfama (the old Jewish quarter).

3. This silly tapestry that hangs in the Biblioteca Nacional. (I stare at it for about 5 minutes every time I go in there – still don’t know anything about it, even though I probably should!)

4. The quirky, the fun, the gorgeous azulejos.

5. Sardinhas (sardines) – especially from Coffee Mania, my neighborhood café across the street – and serradura "(“sawdust”)— a delightful dessert made from layers of sweetened whip cream and crumbled digestive cookies.

6. The beautiful park with this amazing tree in the Principe Real neighborhood and the Principe Real neighborhood in general.

7. The art! Everywhere! In and on everything! Lisbon’s vibrancy is apparent on every corner and at every turn.

It’s been the sweetest seven days – and I am so excited for more. Até amanhã — until tomorrow!

Picking Up on Picart, Pt 2

If you’ll allow me, I’d like to start this blogpost with a little thought exercise. You’re welcome to just do this in your head or write down what you think of on a pad and paper if you’d like. You can close your eyes or keep them open, getting comfortable in your seat. Take a deep breath and clear your mind.

……

I want you to think of a meal. It can be any meal – your everyday dinner with the family, a quick snack break between the many activities in your day, or it can be the celebratory feast of a special day – a holiday or otherwise. Focus on the image – it can be a memory or an imagined meal.

……

And now I want to know: what does the table in front of you look like? Is it a holiday banquette, lined with a fine tablecloth and the best silverware, dotted with flowers and pitchers of special beverages? Or is it a simpler affair – just a seat at the counter with day-to-day dishes atop a place mat or, is there even a table? Are you at a bar or a café? What do you smell? The savory unctuousness of a long-simmering dish in the oven, awaiting its moment of “oohs and ahhs”? Or is it something sweeter, homier – like the sharp warmth of morning coffee or the freshness of a crisp apple, just sliced for an afternoon snack? I want you to focus on these sights and smells until you can almost taste them, and then take one last look at the meal all around you: the people as much as the food. And now tell me, how does this change how you understand this meal, this memory, this imaginative act?

…………………………….

Thank you for going on that little journey with me. Continuing on my discussion from yesterday, it is exactly this last question I asked you that I want to reframe in connection to Picart’s print: how does focusing on food change how we understand a text (a book, a film, a piece of art)? My argument is, probably unsurprising, quite a lot.

Returning to the context of Picart’s print, we’ve already discussed his tendency to visually present Judaism in a way that was not as seemingly neutral, even positive, as many scholars believe. This is as true when it comes to the cover of his series, as Samantha Baskind discusses, as much as in regard to his differential and much more infrequent treatment of the Portuguese Jews’ Ashkenazi coreligionists in Amsterdam. To quote Baskind yet again: “odd that the Ashkenazim should appear so infrequently, because by the mid-eighteenth century the balance of Amsterdam’s Jewish population had changed: of 13,000 Jews in Amsterdam, 10,000 were east European” (Baskind 42). In that way, as I’ve well established in previous posts, we can’t take Picart’s imagery as totally neutral.

The Sephardim, again.

The comparably “uncouth” German (Ashkenazi) Jews, represented here in a wedding scene in Picart’s series.

But picking up on my last post, and focusing on food in particular, can add even further nuance to the scholarly discussion of Picart’s work – not to mention, offers critical clues into if there existed a coherent sense of “Portuguese Jewish cuisine” at all. Turning back to the print (the version taken on my iPhone naturally ;) ). I’d like to just that: focus on the food. There is a variety on the table, but the table isn’t overly laden. In the very center sits a dish that almost looks empty; to the right of the empty-looking dish, there’s a mass of purple and pink, dotted with circles; to the left, a green shaggy tangle of something. Just below sits a recognizable sight to anyone who has been to a seder: a dish with an egg (presumably hardboiled) and a shankbone. The most unfamiliar item on the table, surprisingly, is the matza: what looks like a half-circle of it with elongated holes sits casually to the right of a silver pot, diagonally oriented across the table from what could be its other half in the hands of the man at the head of the table, breaking off another piece to hand to what seems to be his wife. In the corner, near the fire, it is possible to see more matsa (especially in the photo I took, it must be said), swaddled in a blanket and tucked in a basket. The abundance of matsa, the richly appointed silverware, and the clothed table all indicate the wealth of this family, even at this early stage in the meal. This is further emphasized by their fashionable, well-tailored clothing and the presence of our friend in the low bench at the forefront of the image, most likely a servant with roots in a Dutch or Portuguese colony (indicated by his turban and slightly darker skin — perhaps hinting at an “exotic” origin — shout out to Vonnie for her theory about him!), pulling wine out of barrel of water where it was kept cool.

The numbered dishes.

Our mystery friend with the wine.

The swaddled matsa.

Again, all the signs here point to the “model minority” representation of Portuguese Sephardim that was so common in Picart’s renderings of their public life as much as in the work of other contemporary artists, who as Baskin shows also employed a naturalistic style in their depictions of the community’s synagogue and public rituals. But focusing on the food offers some nuance to this idea, put forth by Baskin and others. For example, it is notable that Picart includes a key for his reader, numbering each dish and explaining its contents. He includes an explanation of the hard-boiled egg, the bitter herbs (the green stuff), a delicious-sounding charoset (the purple stuff: figs, apples, almonds, cinnamon – all cut and cooked together), and – of course! – the matsa, what he notes is “the bread of Passover.” More than its informativeness, I am struck by the fact that Picart numbers and explains the food particularly – almost as if it is the only aspect of the image different enough to require explanation.

Picart’s text at the bottom of the image with a description corresponding to each numbered plate in the etching.

And while certainly the whole gestalt of the image communicates wealth, including the expensive fruits and nuts in the charoset, his depiction of them in a moment of breaking bread signals to me that Picart purposefully drew his viewer’s focus to the food for its communicative, boundary-hopping power. This feels all the truer knowing that Picart actually went to the house of a Portuguese Sephardic Jewish family, specifically that of Moses Curiel, to experience a seder firsthand. Even though Curiel was notably quite wealthy – Tirtsah Levie Bernbaum notes he was a merchant connected to Brazilian colonial trade and paid a large sum to lay the first stone of the Portuguese synagogue, the Esnoga – I am struck by the notably casual way Picart depicts them: handing bread to one another, crossing arms to hold a Haggadah together, looking at the man in the second chair from the left (presumably Curiel) to continue leading the story, the silverware arrayed as if it will just be used in the making of a Hillel sandwich. All details that make it feel, at least to me, like Picart is there in the room, just having gotten up to take a quick sketch of his hosts before rejoining them and grabbing a piece of matsa himself.

The aforementioned silver, and to the left, intertwined hands on the haggadah. To left below, the casually placed silverware.

This is how focusing on the food allows us to nuance what earlier scholars have claimed about this image and the Portuguese Sephardim it depicts. And it is the one in the set that has consistently been written about less in the scholarship than all the other, more public-facing representations of this community. And because of this I would argue that it offers a different way of understanding Picart’s relationship to his Sephardic subject -- not to mention it also provides a killer charoset recipe for next Passover ;) – which in studying Sephardic history, can often be as important as the primary source material itself.

There’s more to be said, but for now I will leave it here. More again tomorrow! In the meantime, feel free to let me know what meal you thought of during my little thought exercise down in the comments below or through a direct message. Besinhos (little kisses, a customary goodbye) from Lisbon!

Picking Up on Picart, Part 1

As promised, today I am picking back up on the thread that I left untied with our friend Bernard Picart. I thought about him and his print all day, as I had a sweet and slow Iberian Sunday: grocery shopping and laundry in the morning, an afternoon visit to the very fun LXFactory, and a relaxing shady return to the Fundaçao Calouste Gelbkenian garden. All things — perhaps excepting the laundry and the groceries — that one should do on a trip to Lisbon.

Back to our old friend — a little visual reminder :)

Tourism recommendations aside, part of the reason that Picart was on my mind all day was due to the fact that Lisbon is an incredibly aesthetic city. And I don’t mean aesthetic to mean curated, or simply hip – which of course it is – but I mean it in the sense that at every step in this city, there is art. There are images, graffiti, art displays, designs, random collections of things everywhere here. A lot of it is very cool, some of it is meh – but all of it contributes to a sense that art is part of the daily fabric of life here.

A particularly Sam the Eagle-themed graffiti at the LXFactory.

While of course it may be the self-selecting experience of someone who admittedly gravitates to all things art-related, all of the art that was part of my daily experience got me thinking about the fact of Picart’s project: to represent an Other’s “daily” experience – specifically that of the Portuguese Jews. The print for which I battled the obstinate archivists at the Biblioteca Nacional, though depicting a ritual meal for the holiday of Passover, was really just one within a series of etchings representing different facets of Portuguese Jewish life in Amsterdam. I put the daily in quotation marks because the etchings don’t really show daily life – they include images of the dedication of the main Portuguese synagogue; the holiday celebrations of Sukkot and Rosh Hashanah; the preparations for these special days as well, as in one etching depicted a game-like Portuguese Sephardic ritual to “inspect the leaven” i.e., search out the hamets (leavened products like flour and bread) to clear it out for the holiday. But taken together, I find that they do give a sort of broad glimpse into what it was like for this community to “do Judaism” in a regular, ritualized way – seen through what Samantha Baskin, in her article about this group of etchings, so eloquently calls “Picart’s favor for the normal.” For this reason, I find these etchings so compelling even, as we should remain equally aware of Picart’s supersessionist, eighteenth century perspective – as you may recall, the one that ultimately viewed Christianity as the ultimate improvement on Judaism.

Picart’s etching “The Sound of the Shofar on Rosh Hashanah” (ca. 1733-1739). Source: Wikimedia. I love the different ways each man is sitting as he listens to the sound of new year.

Picart’s “The Meal of the Jews During the Feast of the Tabernacles” (ca. 1724). Source: Wikimedia. There is food in this one as well, though it seems to serve a different purpose than in the Passover etching — more on this soon.

Among these different etchings, though, this Passover meal particularly stands out as an ever so slightly more intimate form of normalcy. The other etchings tend to catch the community at their most formal and outward-facing; in the etching of the synagogue dedication, for example, the grand scale of the building is balanced by well-dressed women and men exchanging pleasantries over the separating wall. Even the more “internal” images depict this community as ideal in their formality; Baskin points out that this is notably different than the prints depicting Ashkenazi families, who are often depicted as boisterous and messy. Unlike their Portuguese Sephardic neighbors who appear as quiet, well-dressed in Dutch fashions, and decorous, their Ashkenazi counterparts do not visually play the role of the “model minority.” There’s more to be said on this difference and why Picart made it so visually obvious -- but for the sake of brevity, I will just say that for all of these reasons, this scene of a Portuguese Sephardic family smiling and breaking matsa around their family dinner table stands out to me as a shade more intimate than the others in the series. In Picart’s images, just as in the art that caught my eye around the streets of Lisbon today, there are not neutral messages. And I believe that an important part of this is the presence of food as a medium expressing and giving place for this intimacy — in Picart’s work as much as in Lisbon street art.

Hands touching in Picart’s etching.

An embrace at the LXFactory.

Since it is late here, for now I will leave it here. But in my next post I’m going to continue this discussion of this image and specifically how when we focus on the food in it, so many more understandings of the etchings’ implicit and explicit messages become possible – plus, there will be some discussion about our mysterious friend with the wine from a couple posts ago. So, if you have any hypotheses on him, feel free to comment below or send me a message! I’ll compile them to include in my next post and, who knows, you might even get a shout out ;)

Until then – good night!

A fabulous food-themed mural with a social conscience outside of the LXFactory.

Even scholars take breaks... or do they?

I must plead your forgiveness today, my dear reader. I know that I promised last night that I would continue on the story of the Picart print I wrote about yesterday. And to make it up to you, I pinky swear promise I will pick up where I left off on that story tomorrow (I promise to do so especially to my friend Gordy who has been dutifully and delightfully reading my posts everyday – hello dear Gordon!). But today, quite honestly, I took the day off to be a tourist and get a feel for Lisbon. And so, instead of continuing with the Picart story in this post, I thought I’d share some pictures – a little photo-essay if you will – of my adventures today. Thank you for indulging my day off whims :)

Though, funnily enough, while I took this day innocently believing that I would not find anything related to my research, in the customary way of the universe, I actually found a few things very related to my research, namely a copy of the narrative drama/play O Judeu (The Jew, 1966) by Bernardo Santareno (pseudonym of Lisboeta psychiatrist, António Martinho do Rosário). It was the first book I laid my eyes on while perusing tables of a street book fair I happened to pass by walking through the Chiado neighborhood. I have a feeling I will definitely be writing about this play once I read it. So despite my best efforts, ultimately this scholar did not have quite the day off she expected ;)

For this post, though, I thought I’d just share a little taste of my wanderings around beautiful Lisbon today: from the Museu da Farmácia (Pharmacy Museum) in Baixa-Chiado to the Fundaçao Calouste Gelbenkian to the north of the city in the Azul neighborhood. I hope it feels like a little mini tour for your Saturday :) Back to regularly scheduled programming tomorrow!

Bonus: while you look through these photos, I thought I’d offer a mini-soundtrack inspired by the fabulous concert I saw this evening (for free! in the open air!) in the garden of Fundaçao Calouste Gelbkenian. The song is “HEADS or TAILS” by the Lisboeta artist The F. Libra. Here’s the link.

A beautiful view and apt phrase from the Miradouro de Santa Catarina.

An open air book fair in Chiado.

A copy of O Judeu, surely the subject of future posts.

Fun, medieval-ish graffiti near the Elevador da Bica.

A cute waiter and chef duo.

A sweet bite on a break from walking the hot city… very important research ;)

A sweet vintage sign in azulejos for water, aguardiente, and liquors.

A vintage apothecary flask for vanilla at the Museu da Farmácia.

What today was (“good day”).

In the heat of the archive

Today was unbearably hot in Lisbon. So I, like any totally normal person (right? Right?) went to the library. And spending the majority of my day in the air conditioned stacks or, well, really the air conditioned reading room, I finally had a research breakthrough today! Unlike my blogpost on Wednesday, in which I wrote about the frustrations and challenges of working in the archive, today I was actually able to see a document up close and personal (huzzah!). I know I will sound like the biggest nerd on the planet when I say this, but there is truly nothing like seeing a historical document/manuscript/image up close – the experience is so essential to research, because it always acts as a reminder that these inanimate objects stored in the stacks were once living, breathing objects that were held, used, and formed part of the intimate lives of people before us. Despite the struggles of archival work – not least of all the particularly frustrating gatekeeping of the archive here in Portugal (a rant for another time) – it is these moments of experiencing this aliveness of the documents that make it all worth it.

And when it came to the document I saw today – the Bernard Picart print I discussed in yesterday’s post – it really made all the difference. I plan on writing more about the food in this print in a following post, but because it’s a bit late here I just want to highlight through some comparative images the drastic difference between the digitized image that was available to me through the online catalogue of the Biblioteca Nacional and the real-life document, up close and personal with images taken on my Iphone.

As a reminder, the original print digitized at the Biblioteca Nacional.

A screenshot from the digitized — begs the question: what is he reaching into?

A screenshot of the silver cupboard behind the diners.

The image I took of the print on my Iphone today at the BNP.

The same section, from my own photos, showing that this figure seems to be grabbing wine bottles from a barrel filled with water.

A much more clearly luminous silver display in my own image of the print.

I hope it translates over the internet, but I was truly astounded by the difference between the two versions. To me, looking at Picart’s print in real life, it was so much more luminous — as if the image itself glowed. It allowed me to not only pick up on many more food-related details that I will explain soon, but to also appreciate Picart’s artistry: between the lines of his cross-hatching I could feel the glow of the candles gently illuminating the room of the family as they broke their matsa and passed it around the table. I hope you can see the difference too – and I’d love to hear your impressions of the image, if so! Feel free to leave a comment below or send me a message with what you think of this print, whether you see the difference, if you think it matters, or any other impression you have upon a first look at these photos. For now, I’m off to bed – boa noite!

PS — thanks to a note from my beloved friend and advisor Gloria Ascher, I have changed the spelling of the word from “matzo” to “matsa” to reflect more authentically the Sephardic context of my subject. Mersi muncho (thank you), Gloria, for your comment!

Bernard Picart and the Seagull Method

On this third day in Lisbon, I decided to take a different tack. I woke up a little later, had a slower morning, and instead of heading to the archive, I steered myself towards another part of town: the charming Principe Real neighborhood, to a small, funky café (with internet!) called the Seagull Method. Naturally, I’m sure you are thinking Sara, what the heck does an oddly named café have to do with your research?! And while you are not entirely wrong in asking such a question, I myself am pleasantly surprised to say quite a lot.

On a completely practical level, this cute café (which I highly recommend for anyone passing through Lisbon – their menu is fab!) gave me a pleasant backdrop against which to do some of the more unglamorous part of research: the reading part. But the café also had a very cool look, and I was struck by the connection between the particularly aesthetic environment I found myself in and my reading of the day.

In particular, I was reading an article by Samantha Baskind about the cover image of a set of prints by French artist Bernard Picart. For some (very brief) context, in the mid-18th century, Picart fled to Amsterdam after becoming a Huguenot and within the context of this (more relatively) religiously tolerant environment. The Netherlands had at that time issued a policy of religious tolerance – that is, of both Catholicism and Protestantism, unusual compared to other regions at the time. Within this context, and as a sort of religious refugee himself, Picart produced a whopping 7-volume series dedicated to the depiction of world religions, entitled Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde (Ceremonies and Religious Customs of All the People of the World, 1723 -1737). Baskind’s main argument about the cover image, which depicts a victorious Christianity sitting in a seat of prominence surrounded by representative figures of the other world religions, offers a tempering response to previous scholarship on it: while previous scholars have understood the work (and its cover image) to promote a sense of Picart’s own toleration of non-Christian religions, Baskind explains that we must understand the image within the supersessionist thinking that marked Picart’s time and most likely his artistic communication. In other words, the image promotes a vision of Christianity as the theological improvement/resolution of Judaism. I find her argument compelling, not the least of all because in the image, allegorical Christianity is actually stepping on Judaism. There are more words to say about this, but for the sake of brevity I will just say: not great.

Screenshot of Bernard Picart, Tableau des principales religions du monde, frontispiece for Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde, 1723. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Note Christianity in the middle right field of the print and Judaism, holding a scroll with Hebrew on it, underfoot.

A very different aesthetic offered by the graphics at the Seagull Method.

So, back to that most essential of questions that started this post – the research connection. The linchpin here can be found in another print of this series, which depicts a family of Portuguese Jews sitting at a dinner table eating during the Passover Seder, entitled Le repas de Paques chez les juifs portugais (The Easter (Passover) meal in the house of the Portuguese Jews). This image is notable not only for what scholars consider its accurate depiction of the dress and mannerisms of Portuguese Sephardic Jews living in Amsterdam at the time – many of whom arrived there after a long journey of expulsion and conversion in what is known as the Western Sephardic diaspora – but also, and particularly for my purposes, it is one of the few images that exist of Sephardim and their food. The family sits around a table that is set and laden in the middle with the seder plate and what presumably is charoset and what seems from the digitized image to be greens of some sort; the lady of the house takes a piece of broken matzo (presumably of the afikoman, the middle matzo) from her husband at the head of the table. It is a remarkable image that only the other day I discovered was housed in the Biblioteca Nacional where I am working and it is one that I hope to get to see up close at some point this coming week -- if the archivists let me! In the meantime, though, I may just have to go back to the Seagull Method Café and stare instead at the very cute prints of other, presumably-not-Portuguese-Jewish people hanging on the wall.

Bernard Picart, Le repas de Paques chez les juifs portugais, 1725. Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, Lisbon.

Research Revelations, or why in-person research is always surprising

Hello friends! I am back with day 2 of my paragraph writing series while in Lisbon. First, I just want to say a huge THANK YOU to everyone who has read the first post – I have been so grateful for all the enthusiasm for this little ol’ idea of mine. Yesterday, I gave a bit of a high-level overview of the project that I’m hoping to do while here. Yet – as turns out to be true with so many things in life – ideas can be very different than the reality. I don’t say this to be entirely cynical, but rather after a somewhat frustrating day at the archive that proved to be a good lesson in why this kind of research can be challenging – yet followed by a different in-person experience that simultaneously demonstrated why it is so critical to still visit the place where this research can be done, especially when said research is connected to historically marginalized or minority communities.

So – the reality. Today I arrived for the second time at the Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal (The National Library of Portugal), where I hoped to gain physical access to a variety of documents that I expected would be helpful to my exploration and eventual re-creation of the experience and recipes of medieval Portuguese Jews. While soliciting the funding for this project, I had identified a few documents that I thought would be useful by searching the online archive. Before even arriving to the archive, though, I was notified that the documents I wished to see (which included a rare 16th century reproduction of a Hebrew Bible dedicated to the one and only Doña Gracia Mendes, the famous Portuguese Sephardic philanthropist and literal Renaissance woman) were not available for my physical perusal. Not to be deterred, I determined that once I arrived at the library I could try to get access to a different set of documents, ideally ones that I had not yet found in my online pre-search. Despite my best efforts today, I wasn’t able to see anything in person.

But – don’t despair, fair reader -- today was not completely a loss! In fact, I had better in-person success with a delightful afternoon visit to the Jewish Cultural Center on Rua Judiaria (Street of the Jewish Corner) in the Alfama neighborhood of Lisbon. I was put in touch by an old friend (hi Ashley!) with my new friend Luciano, who runs this center as what he calls a meeting place and a space of dialogue for the modern Jewish community in Lisbon. We had a lovely chat, exchanging tidbits about what being Jewish on the Iberian Peninsula means these days and the irony of the fact that judiaria, the word that once referred to the Jewish quarter found in almost every town in medieval Portugal, now denotes “a mess” in modern Portuguese (interestingly, the type of mess relevant only to young children and drunken adults). In a physical manifestation of this change over time, the term now only pertains to one street in modern Lisbon. I have more thoughts on this to share in future posts, but I will leave it here for today with my excitement for future in-person research revelations and delightful surprises like this one.

The front façade of the Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal.

As a contrast, the welcoming-but-subtle front door of the Jewish Cultural Center on Rua Judiaria.

The sweet mosaics put up by Luciano outside of the JCC next to a hunk of the mountain upon which the buildings of Rua Judiaria and the old wall of the city still sit.

Activating Archival Ingredients: In Search of Medieval Portuguese Jewish Food and Identity

Bom dia (good day) – or really, I should say, boa noite (goodnight) as I write this at 11 pm. I’m currently in Lisbon, writing to you from my cute Airbnb in the Bairro Dona Leonor neighborhood a few miles north of the city center. Why, you may ask, am I in Lisbon? Well, I’m here on a trip to conduct research on the food and foodways of the medieval Sephardic community here. I’ve been lucky to be generously funded by various fellowships from the University of Minnesota to do this research, and I’ll be spending the next month trying to learn as much as I can about the intersections of Portuguese Jewish history, food, and identity as a part of the first phase of my dissertation research. As a part of this project, and as a way of reflecting on my time here, I thought it would be a sweet idea to write and post a paragraph on my blog every day summing up my impressions, findings, and – let’s not forget! – delicious bites in this beautiful country. My intention for these paragraphs is not only to keep track of all these wonderful tidbits in a casual, not-totally-academic way, but also to be able to share them with those in my community and beyond who might be interested in what I’m researching.

To start, I thought it would be helpful to give a little bit of context for this research project. As many of you know, I specialize the culinary heritage and cultural identity of medieval Sephardic Jews for my PhD at UMN. While it may not seem so, just this phrase alone brings with it a whole host of complicated definitions, not the least of which is the term “Sephardic:” to some scholars (and members of the broader Jewish community), this term simply means “non-Ashkenazi” (non-Eastern European – although there’s complications to that term too that I won’t go into here!); to others, such as Paloma Diaz Mas and Jonathan Ray, this moniker applies only to the generations of Jews descended from those who were expelled from Spain in 1492. As both Diaz Mas and Ray clearly state, the Jews that lived on the Iberian Peninsula before 1492 can be referred to simply as “Spanish Jews.”* Needless to say, this denomination brings with it an abundance of complications, not least of all because it totally excludes the historic experience and identity of the Jews that lived in the geographic area now known as Portugal during the medieval and early modern periods. It is the experience of this community, as expressed through and with food, that I am hoping to find through my research on this trip, to expand the often-narrow discussion of medieval Iberian Jewish identity, both within and outside of the scholarly world.

This research on the medieval Portuguese Jewish experience and culinary identity not only comes from my desire to bring further nuance into the historic discussion of the medieval Sephardic community (not to mention that of its subsequent diaspora) but I see it as intimately related to the myriad ways Jewish identity exists and is expressed within the context of modern Portugal as well. Having lived in Spain, I witnessed firsthand modern Spanish Jewish life and its complicated connections to Spain’s Sephardic past through the experience of my beloved Comunidad Judía Reformista de Madrid. While even in my first 24 hours here I am already realizing the many ways in which Portugal and Spain are two quite distinct countries (for one, Spanish and Portuguese are, not to make a vast understatement, linguas muito diferentes**), I do have a feeling that the two countries do share some similarities, particularly when it comes to their Jewish past -- not the least of all how the idea of what the medieval Portuguese Jewish community was might affect the Portuguese Jewish community that currently is. So, in addition to my historical work through archives, I’m also keeping my eyes and ears attuned to ways these medieval imaginaries of Jews and Jewishness play out in the modern day-to-day here in Portugal. (For those who are interested, these archives include Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, the Arquivo Nacional Torre do Tombo, and the municipal libraries of Évora and Loulé – I can share more on these in the future if it’s of interest!).

Now being three paragraphs over my proposed daily allotment, I will conclude this post here. My personal goal is to share a little something every day, as a way of keeping track of my ideas and the (hopefully many) interesting tidbits of information I expect to find while in Portugal -- whether a photo, a few words, or perhaps even a recipe J Even if the history isn’t your thing, I do hope you’ll enjoy these little petiscas*** as a fun daily mini-vacation. And if you have any questions, ideas, or suggestions of where I should go while here in Portugal, please let me know! Now, boa noite for real, and until tomorrow!

*Suggested readings for those who are interested: Paloma Diaz Mas’s Sephardim: The Jews from Spain (1992) and Jonathan Ray’s After Expulsion: 1492 and the Making of Sephardic Jewry (2013)

**Portuguese for “very different languages”

***the Portuguese equivalent of tapas, or small bites/plates of food

Below: some of my first bites in Lisbon; from left, a sardine for dinner, and a seafood rice for lunch at the archive.

A fun collaboration + a break fast recipe

Happy Wednesday everyone! In anticipation of Yom Kippur, I collaborated with my friend Liz from Kosher Like Me for a delicious, Sephardic-inspired break fast recipe.

Head here to check out the recipe and the cool back story behind this Revanada de Parida bread pudding. Enjoy and may your fast be an easy one!

Some blog updates!

As they always say New Year, new blog, right? Right! In the spirit of ~newness~ I want to share with you all some updates that this blog is currently undergoing.

First off, as some of you may have already noticed, there's a Press page of the blog!

Now you can easily see all the places where Sara is spreading the Boka Dulse love!

Yahoo! On this page you can read, listen, and watch all of the different media publications that have featured Sara, including her upcoming biweekly radio show (in Spanish) about Jewish food history for RadioSefarad.

Additionally, you'll find some new images, restaurant recommendations, and sites on the Travel page.

Looking for travel inspiration and great tips? The newly-updated Travel section is where to go!

Now you'll be able to explore my images and tips from my travels during this past year. Cities covered include: Madrid, Ávila, Burgos, Castilla, Granada, Lisbon, Salamanca, Tenerife, Toledo, Valencia, and Zaragoza. And if you're planning a trip and have any questions for me, feel free to write me a message .

This could happen at your synagogue! Sign up here to have me come teach.

Finally, a big update for this blog can be found here. I've been doing a great deal of teaching over the past few months, and I'm offering my skills to any Jewish community that wants to come have me teach! Looking for an interesting way to engage synagogue members in Jewish learning? Want to find new ways to engage and interact with Jewish culture and community? Whether you're interested in Sephardic Jewish food history or want to know more about general Jewish food history and identity, I'd be delighted to come teach at your synagogue today. Customizable to your community's needs and schedule, I offer the options of one-off classes as well as class series. Classes include two parts: one on the theory of Jewish food and identity; the other dedicated to cooking the dishes we discuss in class. Contact me here today to set up a cooking lesson with me!

Anyway, that's all for now folks! Keep your eyes peeled in the next couple of weeks for more new and exciting stories and history from your favorite Jewish food history blog, Boka Dulse.

Abrasos,

Sara